Story Of How British Left India?

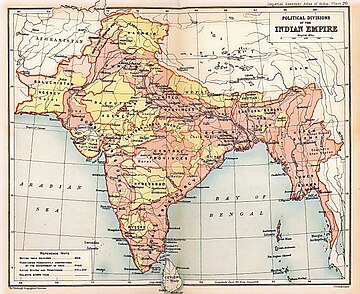

The story of how the British left India is a complex narrative woven with threads of ambition, conflict, and the relentless pursuit of freedom.It begins in the early 17th century when the British East India Company arrived on Indian shores, initially seeking trade opportunities.

Over time, this commercial enterprise morphed into a powerful political entity that would dominate large parts of the subcontinent. The East India Company’s rule was marked by exploitation and disregard for local customs, which sowed the seeds of resentment among Indians.

As the 18th century began, the British East India Company expanded its control through a combination of military might and strategic alliances. The pivotal moment came in 1857 with the Indian Rebellion, also known as the Sepoy Mutiny.

This uprising was fueled by discontent over British policies and cultural insensitivity. The rebellion was brutally suppressed, but it led to significant changes in British governance. In 1858, direct control of India was transferred from the East India Company to the British Crown, marking the beginning of the British Raj.

The Raj was characterized by a duality; while it brought some infrastructure development and modernization, it also entrenched social divisions and economic exploitation.

WikiPedia

The British implemented policies that favored their own interests, leading to widespread poverty and famine in India. The economic exploitation was accompanied by cultural imperialism, which aimed to reshape Indian society according to British ideals.

By the early 20th century, a growing sense of nationalism began to take root among Indians. Leaders like Mahatma Gandhi emerged, advocating for non-violent resistance against British rule. The Indian National Congress, founded in 1885, became a platform for expressing nationalist sentiments and demands for greater autonomy.

The struggle for independence gained momentum in the 1920s and 1930s as more Indians became involved in political activism.The impact of World War II on British India was profound. The war strained Britain’s resources and exposed its vulnerabilities.

In 1942, during the height of the war, Gandhi launched the Quit India Movement, demanding an end to British rule. This movement galvanized millions across India but was met with severe repression by the British authorities.

Despite this crackdown, the movement highlighted the determination of Indians to achieve independence.

As the war concluded in 1945, Britain found itself weakened economically and politically. The Labour government elected that year recognized that maintaining control over India was no longer feasible. The call for independence had grown too strong to ignore.

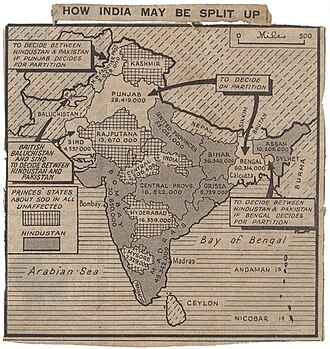

In 1946, Britain announced its intention to grant India independence, setting off a series of negotiations among Indian leaders.However, these negotiations were fraught with tension. The Muslim League, led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, demanded a separate nation for Muslims, fearing that they would be marginalized in a Hindu-majority India.

This demand for Pakistan created deep divisions within Indian society and complicated discussions about independence.

Partition of India

By WikiPedia

In March 1947, Lord Louis Mountbatten arrived in India as the last Viceroy tasked with overseeing the transition to independence. Mountbatten quickly realized that the differences between Hindus and Muslims were irreconcilable at that moment in history.

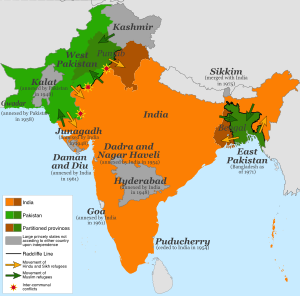

He proposed a partition of India into two separate nations: Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan. This decision was met with mixed reactions; while some welcomed it as a solution to communal tensions, others decried it as a betrayal of the idea of a united India.

The announcement of partition on June 3, 1947, set off a frantic race against time to demarcate borders between the new nations before independence was officially granted on August 15, 1947. The hurried partitioning process was overseen by Cyril Radcliffe, who had little knowledge of Indian geography or communal demographics.

As he drew lines on maps dividing Punjab and Bengal, chaos ensued.The consequences of partition were catastrophic. Millions found themselves on the wrong side of newly drawn borders—Hindus in Pakistan and Muslims in India—leading to one of the largest mass migrations in history.

Between 12 and 20 million people were displaced along religious lines as a result of the partition, which led to severe refugee crises in the newly formed dominions.

The British India was divided into the Union of India and the Dominion of Pakistan in 1947, it was known as the partition of India. Today, the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, and the Republic of India and the Dominion of Pakistan comprise the Union of India.

Bengal and Punjab were split into two provinces according to district-by-district Hindu or Muslim majorities as part of the partition. In addition, the Indian Civil Service, the British Indian Army, the Royal Indian Navy, the railways, and the national treasury were split between the two new dominions.

The British Raj, or Crown control in India, was abolished as a result of the partition, which was outlined in the Indian Independence Act 1947. At midnight on August 14–15, 1947, India and Pakistan, two sovereign nations, formally became one nation.

There was also widespread violence, with estimates of the number of people killed before or during the partition ranging from several hundred thousand to two million. The bloody separation engendered an environment of animosity and mistrust between India and Pakistan that still taints their relationship today.

An estimated 15 million people were displaced as they fled their homes amidst rising communal violence. The resulting chaos led to horrific sectarian violence that claimed hundreds of thousands of lives; estimates range from 200,000 to two million deaths during this tumultuous period.

In a state of sorrow and bloodshed, both countries struggled with their new identities as families were split apart and communities were destroyed by mistrust and violence.

In India, leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru emphasized unity and secularism as foundational principles for the newly independent nation. Meanwhile, Pakistan’s creation marked a significant moment for Muslims who sought self-determination but also faced challenges in establishing governance amid widespread upheaval.

The legacy of partition continues to resonate today; it left indelible scars on both nations’ psyches and shaped their subsequent histories. For many Indians and Pakistanis alike, partition remains a painful memory—a reminder of lost homes and lives forever altered by political decisions made far away from their realities.

Radcliffe Line

In sharp contrast with Gandhi’s opposition to partition, nationalist leaders in June 1947 agreed to a division of the country, including Nehru, Valllabh Bhai Patel, and J B Kripalini on behalf of the Congress, Jinnah, Liaqat Ali Khan, and Abdul Rab Nishtar on behalf of the Muslim League, and Master Tara Singh on behalf of the Sikhs.

The proposal called for the division of the Muslim-majority provinces of Bengal and Punjab, assigning the primarily Muslim regions to the new country of Pakistan and the predominantly Hindu and Sikh regions to the new India. Even more horrifying was the community rioting that followed the publication of the Radcliffe Line, the line of partition.

Historians Ian Talbot and Gurharpal Singh described the bloodshed that followed India’s division as follows:

“There are numerous eyewitness accounts of the maiming and mutilation of victims. The catalogue of horrors includes the disemboweling of pregnant women, the slamming of babies’ heads against brick walls, the cutting off of the victim’s limbs and genitalia, and the displaying of heads and corpses.

While previous communal riots had been deadly, the scale and level of brutality during the Partition massacres were unprecedented. Although some scholars question the use of the term ‘genocide‘ concerning the partition massacres, much of the violence was manifested with genocidal tendencies. It was designed to cleanse an existing generation and prevent its future reproduction.”

Independence: August 1947

Before departing for India, where the oath was set for midnight on the 15th, Mountbatten gave Jinnah the independence oath on the 14th.The new Dominion of Pakistan was established on August 14, 1947, and Muhammad Ali Jinnah was sworn in as its first governor general in Karachi. On August 15, 1947, India—now known as the Dominion of India—became an independent nation.

Jawaharlal Nehru was appointed prime minister, and formal ceremonies were held in New Delhi. As the first governor-general of an independent India, Mountbatten stayed in New Delhi for ten months until June 1948.In order to assist the recently arrived refugees from the divided subcontinent, Gandhi stayed in Bengal.

- FOR DEEP INFO VISIT: PARTITION OF INDIA

Discover more from Daily UKUS News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.